I come not to praise nor to bury ultra-process foods. This piece, however, is an indictment of those trying to find a facile scapegoat [1] on which to blame current problems. Those engaging in the “name and blame game” typically use correlation, rather than causal proof, as their sword. For those seeking any culprit or an easy target to blame (or sue) for obesity and metabolic diseases, ultra-processed food (UPF) manufacturers are a dream target.

Witch hunters creating a new social “witch” often ignore science, suggesting simpler, more convenient potential culprits and ignore confounders, luring us down a rabbit hole while diverting us from identifying the true culprit(s) and pursuing real solutions, only to back-track decades down the road.

From a legal evidentiary standpoint, causation is most reliably detected from epidemiological evidence. However, interpretation of those studies is often not straightforward. Among the generally required criteria for interpretation [2] is temporality – the cause must precede (with or without a latency period) the effect. The effect should not suddenly appear, like a time bomb, decades after exposure cessation with no biologically plausible explanation for the delay.

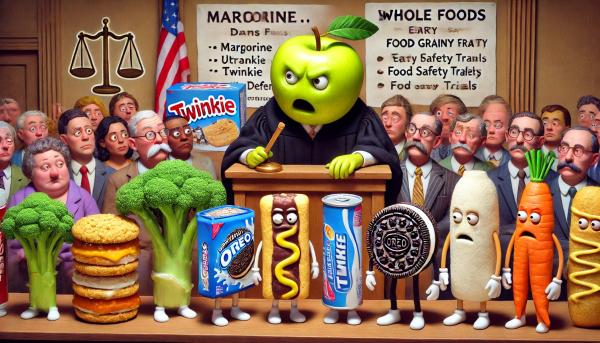

Which came first: The chicken, the egg, or the Oreo?

Obesity is hardly a new disease. But what is new and different are its accompaniments: metabolic diseases such as Type 2 diabetes (T2D) and fatty liver, recently exhibiting a small but alarming increased incidence in youth. Perhaps we can look to the temporality of these accompanying conditions to divine the “causes” of obesity and these metabolic diseases.

So, while UPFs provide a convenient and inviting “witch” to outlaw or control to remedy these potential culprits, does it satisfy temporality and other epidemiological requirements needed to establish disease causation?

The sudden emergence of childhood metabolic diseases seems a bit out of whack with history, mine anyway. I fondly remember lapping up sugary processed cereals, snacks, and soda as a child more than a half-century ago – as did my peers. No mention of metabolic diseases in children was reported then or for decades thereafter. These foods were heavily laced with additives and chemicals, with sugar generally listed as the second ingredient.

Every day in high school, I rewarded myself for surviving boring classes by eating a fried custard donut with chocolate frosting! Yum. Yes – I gained weight. Since this was long before Ozempic, I had to resort to diet and exercise to lose it. And while anecdotal, scores of my classmates who similarly consumed these yummies remained of “normal” weight and free of liver damage.

My favorite cereal, Sugar Frosted Flakes, was introduced in 1952 -yet no commensurate reports of obesity or metabolic diseases were noted then or for decades thereafter.

Many other UPFs surfaced far earlier, without the accompanying diseases we now claim are causally related:

Margarine, perhaps the first UPF, was invented in 1867. The Oleomargarine Act” passed in 1886, tried to label margarine consumption as “unsafe,” as margarine exports rose to almost twice that of butter. Related lawsuits were pursued up to the Supreme Court by early 20th century.

Margarine, perhaps the first UPF, was invented in 1867. The Oleomargarine Act” passed in 1886, tried to label margarine consumption as “unsafe,” as margarine exports rose to almost twice that of butter. Related lawsuits were pursued up to the Supreme Court by early 20th century.

“Fake butter swamped the Victorian-era United States. The new invention was both abhorred and adored. Margarine may have begun in France, but U.S. manufacturers grabbed that bull by the horns and ran with it. An American inventor bought the patent, then patented improvements to the counterfeit butter process.”

Twinkies were first introduced in 1930. The first cry of twinkies-addiction, “The Twinkie Defense,” was raised in 1979 by a man on trial for murder. His defense? That junk foods like Twinkies caused his diminished mental capacity.

The first Oreo was sold in 1912. As Segmenta, a marketing firm, notes, 92% of male cookie snackers ages 16-18 include Oreo as one of their favorite brands. Its use peaked during COVID, spiking again in 2024, long after the obesity crisis was first noted, a pattern discernably different from UPF consumption trends.

Evidence also indicates Oreo-eaters are predisposed to ignore health:

“Oreo snackers are 68% less likely to value health compared to non-Oreo snackers. They’re also 57% less likely to reduce or eliminate sugar in their diets and 15% less likely to exercise or play sports.”

So, which came first, health inattention or Oreo consumption? Are those who consume more sugary foods genetically predisposed, or are they “addicted” to foods that rewire their internal circuits? Are people predisposed to eating sugary foods? While UPF has undoubtedly been linked to obesity and obesity to metabolic diseases, the connection is not direct, a classic indication that confounding may be at work. Let’s look.

Correlation v. Causation

Perhaps the product with the worst rap is Coke. First served on May 8, 1886, at Jacobs' Pharmacy in Atlanta, Georgia, Coca-Cola was created by Dr. John Pemberton as a tonic for common ailments. In the 1960’s Coke was blamed for the sudden increase in polio - just as Coke consumption rose in the summer, so did, almost in tandem, cases of polio.

But what does this tell us? Like ice cream, Coke is heavily consumed in the summer when polio naturally rises due to heat and ease of transmission. Polio is correlated with heat, which, in turn, is associated with consuming more Coke and ice cream, but that doesn’t prove a causal connection. When a factor is related to the outcome and exposure, this phenomenon is called confounding.

The original Coke contained sugar, while today’s version includes the much-maligned high fructose corn syrup. So, perhaps it’s Coke’s fructose that causes our problems. That sounds plausible, except the fructose transition occurred around 1984, more than 40 years ago.

Even the Courts Got Involved- Over a Century Before the Obesity Epidemic Was Coined

The healthfulness of foods “adulterated” with additives and colorants was even litigated -- over a century before the obesity epidemic showed its horns and juvenile metabolic diseases reared their ugly horns.

- An English statute of 1875 provided that: "No person shall mix, color, . . . or order or permit any other person to mix, color, . . . any article of food with any ingredient or material so as to render the article injurious to health."

- In 1904, a British Court addressed whether food colorings impacted the healthfulness of peas. (There, the manufacturer added copper sulfate).

- The case of Lexington Mill & Elevator Co. v. United States, decided in 1914, addressed whether bleached flour was harmful.

- In 1917, the court in United States v. Atlantic Macaroni Co., addressed whether macaroni dyed yellow was injurious.

Temporality in Real Life

The obesity epidemic first gained prominence in the mid-1970s - long after UPF, colorants, and additives appeared in foods. Not long afterward, a connection between UPF and all-cause mortality (not obesity or juvenile metabolic diseases) was determined. However, when confounders are considered, the results are hardly as impressive:

“Participants in the fourth quarter (high consumption of ultra-processed foods) had a higher average BMI. Compared with participants in the first quarter, they were more likely to be current smokers… have a family history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, prevalent cardiovascular disease, and depression. In addition, they were more likely to snack, watch television, and use a computer for longer periods, more prone to be sedentary and nap…..”

The folks consuming the most UPF were walking time bombs, irrespective of food consumption. While a low UPF diet may prolong life, evidence demonstrating its impact on obesity and metabolic dysfunction is weaker, especially in children.

A “small number of other prospective studies in children do not suggest an increased risk [of metabolic diseases] with greater UPF intake.”

Given that the presumed cause (UPF, food colorants/additives) was first introduced over a century ago, without the sequelae we now see, it seems to me that some other factor has intervened to either independently cause the current diseases or exacerbate the impact of the current “witch” products. So, I wonder: are we focused on the correct culprit? The correct causal mechanism? The proper food group? Is there a contribution from genetics? Environment? Lifestyle? Socio-economics? Sadly, no one knows.

Demonizing ultra-processed foods as the singular cause of obesity and metabolic disease may be satisfying, but it’s far from scientifically airtight or even reliable. The truth is far messier—If we want real solutions, we need to resist the allure of the easy narrative and focus on a fuller picture.

[1] Scapegoat is somewhat ironical as its biblical origins refer to a goat (food) “carrying the sins” of the Israelites

[2] Interpreting epidemiological evidence typically includes subjecting the results to a Bradford-Hill criteria analysis, which presupposes compliance with nine factors, one of which is temporality; another is excluding confounders.