Factory farming, particularly in the poultry sector, has long been a cornerstone of modern food production, providing an abundant supply of meat and eggs to meet global demand. However, this abundance has come at a significant cost to animal welfare.

- Poultry accounts for 96 percent of land animals eaten by Americans - a statistic that reflects the popularity of chicken products and the scale at which these animals are produced.

- In just two years, more chickens are slaughtered than the number of humans that have ever lived – a measure of the scale of production and consumption. In producing eggs, traditional practices result in culling 6-7 billion day-old male chicks.

The welfare of chickens is often traded for the economic efficiencies of factory farming—chicks endure stress, pain, and injuries throughout their short lives. Emerging technologies, including in-ovo sexing and vaccination, as well as on-farm hatching, can provide a bit of a twofer, improving the efficiency of production and the welfare of chickens. However, it will require disruption and increased costs.

Poultry Supply Chain

Traditionally, fertilized eggs are incubated in large incubator-like facilities with tightly regulated temperature, humidity, and CO₂ levels. Once the chicks hatch, they are subjected to manual sex sorting and vaccination, both requiring direct human intervention. Chickens destined to be “layers” are sex sorted – males, who do not produced eggs are unnecessary. We have optimized the breeding of layers, so today’s layer produces 300 eggs a year, compared to 150 in 1950. That breeding focus means that males bred as layers, do not grow sufficiently quickly or large enough to make them economically viable, so in addition to being unnecessary, they are unwanted and culled [1]. “Broiler” chickens, growing to four times the weight of a “natural” chicken in 6 to 7 weeks, destined to come to our tables as meat, require sexing because males and females grow at slightly different rates, and separating them by sex allows more precise feeding and “harvesting.”

Sexing

For the most part, sexing baby chicks remains a skill applied by humans – each examining chicks by hand, inherently inefficient, fraught with human error, and of course, the newborn chicks may find this stressful. I’ve written on the topic in the past. However, there are advanced imaging technologies, e.g., MRI and biochemical analysis, e.g., PCR or mass spectroscopy, that can accurately determine the sex of the embryonic, in the egg, chicken.

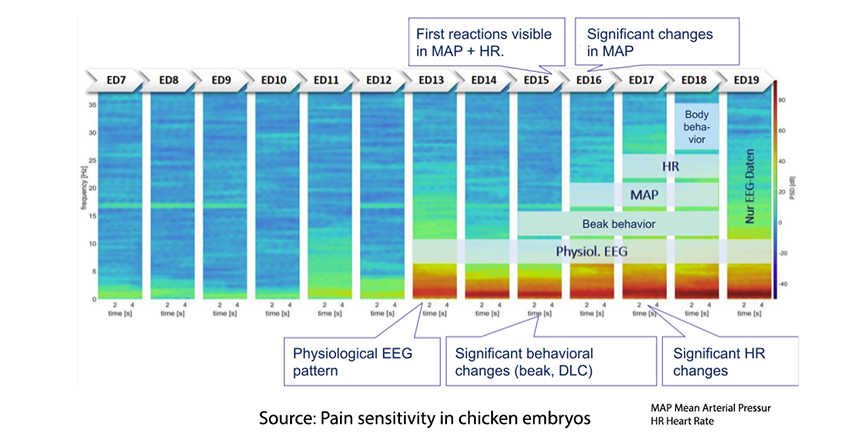

Studies of chicken embryos show that chickens respond to noxious stimuli in mid-gestation. Since culling chickens has been outlawed in Germany, industry studies have established that their first response to noxious stimuli, on EEG, occurs on Day 13 of their 21-day gestation.

From an animal welfare point of view, and yes, I understand the greater context that they will be culled in any instance; Day 12 culling seems the most humane. Both advanced imaging and biochemical determination of sex can be performed, with a high degree of certainty, on that date, allowing these male embryos at least a painless exit. In-ovo sexing is readily automated, reducing labor costs and opening additional incubator space. In Europe, roughly 15% of the layer population is sexed using automatic technologies.

Vaccination

It is somewhat ironic, in discussing chicken vaccination, that there are so many overtones to human influenza vaccination.

- The USDA must approve chicken vaccines, just as the FDA approves human vaccines.

- Avian influenza vaccines, like human flue vaccines, must be directed at a moving target, so vaccination against one older strain is not a guarantee of protection against a newly arisen one.

- As we found with human flu vaccines, it may not prevent the disease but significantly reduce one’s symptoms, creating a possibility of asymptomatic carriers.

- Broilers go from egg to supermarket in about eight weeks, so some may feel that the life window is so small that it is worth the risk, especially given that the Animal Health Protection Act of 2002 in providing the USDA authority to “depopulate” at-risk flocks, indemnifies farmers for those chickens and eggs lost.

- Finally, 18% of our chickens are exported, and given that vaccines may create asymptomatic carriers, few countries, if any, allow the importation of vaccinated chickens.

That being said, in-ovo vaccination represents an advancement in improving chicken welfare. Traditional vaccination methods, which involve handling and injecting live chicks, not only cause significant stress but also result in inconsistent vaccine delivery. In contrast, in-ovo vaccination administers vaccines directly into the egg, ensuring that each embryo receives a uniform dose of the vaccine before hatching. This method has the dual benefit of reducing the handling stress associated with manual vaccination while giving the chick’s immune system a head start in defending against disease. The pre-hatch administration allows the immune system maximum time to develop and respond to the vaccine, enhancing overall health and resilience.

In-ovo vaccination has been used for some time for broilers for our domestic consumption. It reduces labor costs, increases immunization consistency, and doesn’t further stress the chicks. It has not found a similar foothold among the layers because it would mean unnecessarily vaccinating males who will be culled. However, if combined with in-ovo sexing, only the female eggs would be vaccinated, eliminating the additional costs. Getting producers to accept two expensive technologies at once is, in fact, a real chicken or egg dilemma.

Chicken Run

Currently, incubator farms provide newly-born chickens to broiler and layer farms. This involves a truck ride, which exposes the newborns to stress, risk of injury, and exposure to pathogens. On-farm hatching can reduce that stress and risk by transporting them when they are more protected, still in the shell – their version of a child car seat. While we humans may continue to argue over the deleterious effects of stress, chicken farmers already know that stress reduction contributes to better intestinal development, boosting growth, and a lower incidence of diseases, which in turn decreases the reliance on antibiotics and antibiotic resistance. Nowhere is the alignment of animal welfare and economic performance more clearly identified.

Each of these technologies addresses a different yet interconnected portion of the poultry supply chain. Each improves animal welfare and provides downstream economic benefits even with initial costs. It is difficult to see how we can feed ourselves without factory farms.

There is a long history of honoring our food and recognition of food as a gift rather than a commodity. From Indigenous traditions of gratitude and respect to Shinto’s emphasis on harmony in nature to Christianity's acknowledgment of divine provision in the Biblical narratives of manna and the Last Supper to the enduring practices of saying grace, where every meal becomes a sacred encounter with God's bounty. Even our secular Thanksgiving recognizes the gift over commodity. While the specifics vary, several common themes emerge: gratitude for life, respect for the natural world, and recognizing a sacred cycle between humans and animals.

Reverence for the animals we eat can and should influence our behavior. These new technologies may help mitigate some of the negative impacts of factory farming by promoting more ethical and sustainable practices. The transformation ongoing in the poultry industry is a compelling example of how technology can address some of the most challenging issues in factory farming. Embracing these advancements assuages some of the ethical challenges inherent in factory farming and sets a promising course toward a more sustainable and humane food system.

[1] Culled is one of those words that hides its true meaning, like “transporting” in the context of Nazi Germany.

Source: Before they Hatch