Ringing out the old year with a new Nannygate, six plaintiffs' law firms joined forces to sue ten major food and beverage producers [1]. The claim? That (collectively?) they caused the fatty liver disease and Type 2 diabetes of a teenager named Bryce Martinez.

Just how did they do this? Allegedly, by conspiring to produce addictive, dangerous, ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which comprise some three-quarters of the American diet, thereby single-handedly causing the obesity epidemic and 32 chronic diseases. Other dastardly deeds of the defendants include:

- Selective advertising to children, who would then continually nag their parents to buy the products.

- Using research conducted by Big Tobacco regarding improved taste, merchantability, and marketing.

In short, this is a crusade to decimate our food supply, now overloaded with UPFs, ostensibly because all these products are unsafe. Per the complaint, these UPFs were insinuated into our diet in the 1980s in place of “real foods,” resulting in the increased incidence of Type 2 diabetes, fatty liver, and 32 cancers, especially in youngsters. The plaintiffs also claim that efforts to make our foods tastier, creamier, more appetizing, and palatable (as well as longer lasting and cheaper, properties conveniently neglected by the plaintiffs) must be tortious since the claimed risks outweigh any benefits they can identify.

In an artful mélange of attacks claiming the food producers deliberately designed their products to addict the user – juxtaposed with associations with Big Tobacco, guilt by association is insinuated layer by layer. Peeling back the odious structuring of the allegations, repeatedly interposing Big Tobacco’s bad acts with activities of “Big Food,” we can get to the crux of the claim.

Ultra-processed Foods

Most nutritionists agree that excessive intake of UPF isn’t healthy. The AMA limits concerns to excess salt, sugar, and food colorants. While preservatives are noted, their purpose is to extend shelf life and keep the food microbe-free. The solution generally advocated is to reduce, not eliminate, UPF consumption. The WHO and the FDA focus on consuming healthy foods according to their nutritional value. Others advocate a diet that is balanced, adequate, diverse, and “moderate in consumption of foods,… or … compounds associated with negative health effects.”

Rather than warning about UPF, the FDA allows certain foods to be labeled “healthy.” Although what healthy means might be ambiguous, one might reasonably presume that foods without this label are less nutritious. In 2022, the Biden Administration convened a conference on hunger, nutrition, and health. Their monograph references “processed” once – in relation to high sodium content.

The complaint removes the option of choice from the consumer, claiming that UPF is deliberately engineered to be addictive, along with the likes of Tobacco and opioids, making it impossible to resist. And while the complaint focuses on the hypnotic mind-control and marketing tactics aimed at susceptible and suggestive children, especially in the Black and Hispanic communities, the evidence suggests otherwise. “Considering nearly 88% of U.S. adults aren't metabolically healthy and 63% exceed the daily limit for added sugars in their diet,” it would seem that adults are equally susceptible.

Reality Diverges from the Claims

While the complaint references the dangerous additives, colorants, processing, and cheap “non-food” alternatives like fructose, dextrose, and lactose allegedly causing obesity and type 2 diabetes, recent evidence indicates multiple factors, including natural sucrose, driven by genetics.

“[O]ur study suggests that genetic variation in our ability to digest dietary sucrose may impact not only how much sucrose we eat, but how much we like sugary foods.”

- Dr. Peter Aldiss, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham.

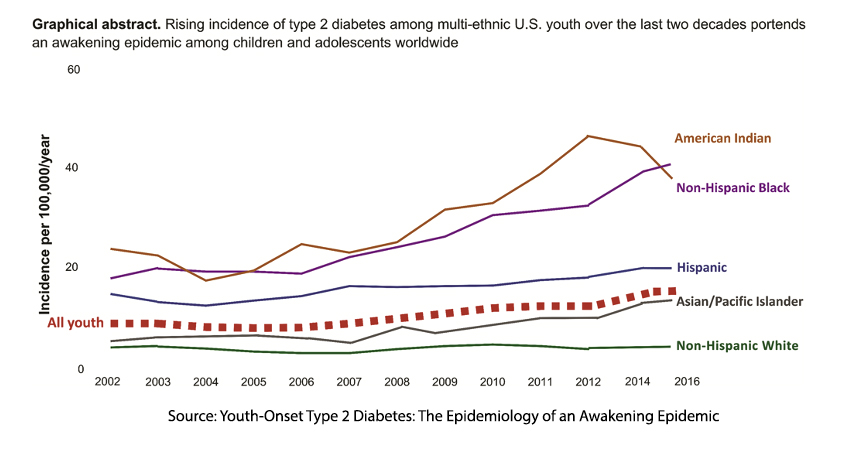

While Type 2 diabetes is indeed increasing in the young, the disease is still quite rare, making it difficult to conduct robust epidemiologic studies or prove causal conclusions. A recent (2023) review of both the limited epidemiology and literature published by the American Diabetes Association dismantles most of the plaintiff’s claims:

While the complaint alleges that the UPF manufacturers targeted Black and Hispanic youth in their advertising, causing this group to have the highest obesity and Type 2 disease incidence, the plaintiffs ignore the finding that rates also escalated disproportionately in Asian/Pacific Islanders and decreased in American Indians. Furthermore, females consistently have a significantly higher prevalence than males. And all this happens without the targeted advertising so maligned by the plaintiffs. So much for the impact of the advertising.

“Traditional diets throughout the world are healthful, even though they diverge widely in their nutrient content. For example, traditional Asian diets are high in salt, traditional Latin American diets are high in carbohydrates, and traditional Mediterranean diets are high in fat. Nevertheless, all promote healthful lives and positive health outcomes.”

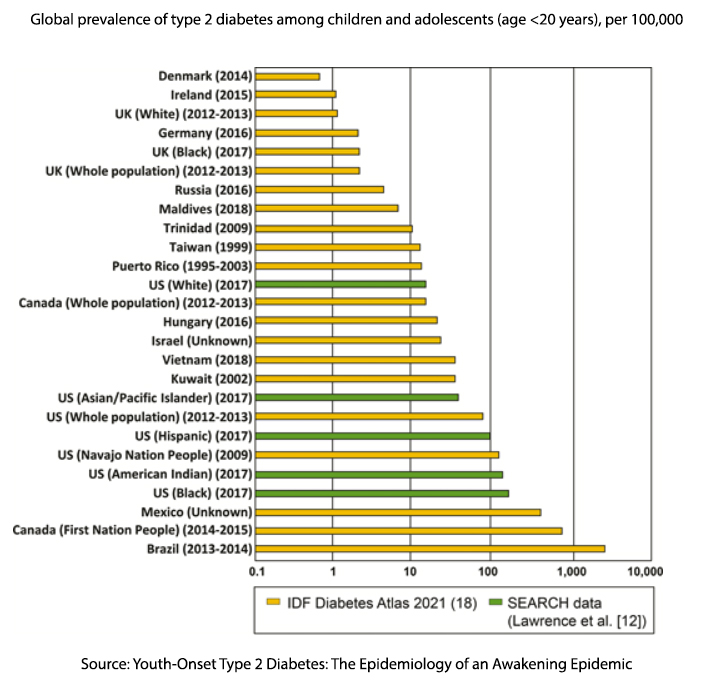

The complaint also “validates” their allegations with the statistic that the majority of the American diet (73%) is composed of UPF, compared to the “healthful diets of other countries, which promote “positive health outcomes,”:

The researchers tell us that “type 2 diabetes prevalence is highest among adolescents in Brazil (33 per 1,000) … and youth in Mexico (4 per 1,000),” both of which implement a Latin diet. The “healthy” Asian diet consumed in Vietnam results in a diabetes level higher than the US white population, as the “healthful” Mediterranean diet does in Israel.

The researchers attribute higher Type 2 diabetes rates to genetic predisposition, heterogeneous pathophysiology of the disease, disparities in socioeconomic status, access to health care, and cultural practices. UPF isn’t mentioned. Indeed, a focus on the price attractiveness of UPF as a driver for consumption in the less affluent (often Black and Hispanic communities) goes unrecognized in the legal complaint as a driver of consumption. [2]

The legal complaint

It is hard to see where the plaintiffs are going with this other than to note that they smell big bucks. At least four different plaintiffs’ firms are trying to join the litigation.

The major allegation is negligence and related claims like failure to warn, fraudulent concealment, and a slew of fillips like conspiracy and acting in concert. Establishing negligence requires proving several elements, including that the defendant knew or should have known of the dangerous consequences of their actions. However, evidence exists in the negative:

“We do not conduct or fund any research aimed at creating dependency upon any of our products, or limiting consumers’ ability to control their eating behaviors.”

- Nancy Daigler, a Kraft spokeswoman

Whether internal documents show the defendants did have actual knowledge of harms might tip the case in favor of the plaintiffs. However, in addition to proving unreasonable acts, the plaintiffs must show their direct (proximate) causal connection with the injury.

Causation

Here, the causal connection is circuitous and based on a series of dubious allegations:

Big Tobacco researched maximizing product consumption → Big Tobacco companies bought food companies → Food companies used Big Tobacco research to intentionally design UPF to hack the physiological structures of our brains. → This knowledge was transferred to other food and beverage manufacturers → The knowledge was used to engineer foods that were as addictive as tobacco or opioids.

As I’ve written, proving causation falls into two categories: general and specific.

- General causation requires proof that, in reasonable doses, the product can cause Type 2 Diabetes and Fatty Liver in kids. That will be difficult given the rarity of “fatty liver” in children.

- After establishing general causation, the plaintiffs must prove specific causation, i.e., that the UPFs caused Bryce Martinez’s diseases in the doses he was exposed to. Given that Bryce alleges he ate at least 100 dangerous UPF products containing these addiction-generating additives (including Pam), allegedly causing his type 2 diabetes and fatty liver, I suspect that will be difficult.

Substances acting in concert can qualify for causation, but you need to know which substances, how each worked, and how much was consumed (dose), and you need to prove a synergistic effect of the constituent ingredients. It’s rather far-fetched to expect a judge to allow 100 products from ten manufacturers to proceed to jury deliberation. However, this case is brought in Philadelphia, a plaintiff’s haven, so all bets are off.

Perhaps what should be of most concern to the plaintiff comes from the researchers' ultimate conclusion:

“In cases of in utero exposure to maternal diabetes ‘offspring … had …[a] 10-fold greater risk of type 2 diabetes by adolescence and young adulthood. Further, maternal diabetes was the single strongest risk factor for youth-onset type 2 diabetes, accounting for most of the increase in youth-onset type 2 diabetes in this population over the last three decades…. Such findings highlight the need to consider exposures and experiences, starting in gestation, if not before conception, for prevention of type 2 diabetes.” [emphasis added]

In the end, the plaintiffs' crusade to blame Big Food for Bryce Martinez’s health woes hinges on a series of insinuations and leaps in logic, from nebulous associations with Big Tobacco to unsubstantiated mechanics of causation. The case casts guilt by association rather than a cohesive legal or scientific argument. Add the sheer improbability of pinning specific health outcomes on a hundred different UPFs based on currently available scientific evidence and the lawsuit seems more about headline-grabbing than justice. While the plaintiffs dream of purging the American diet of Twinkies and Cheerios and pushing prunes, peppers, and pinto beans, they might just be serving up a platter of empty calories to clog the courts. If anything, this spectacle underscores the need for personal responsibility, up-to-date policymaking, and lawyers who understand scientific evidence—not a courtroom food fight.

[1] Post Holdings, Inc. The Coca-Cola Company, Pepsico, Inc., General Mills, Inc., Nestle USA, WK Kellogg Co., And Mars Incorporated

[2] Recently, experts have urged action to break the link between unhealthy food, non-communicable diseases and poverty.