One of my roles is to separate science fact from science fiction. I have found that it often takes longer to debunk bad science than I had anticipated. As is frequently the case, I am late to the party. Consider Jonathan Swift's remarks in 1710, when newspapers were the new media.

“Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it; so that when men come to be undeceived, it is too late, the jest is over, and the tale has had its effect: like a man who has thought of a good repartee, when the discourse is changed, or the company parted; or, like a physician, who has found out an infallible medicine, after the patient is dead.”

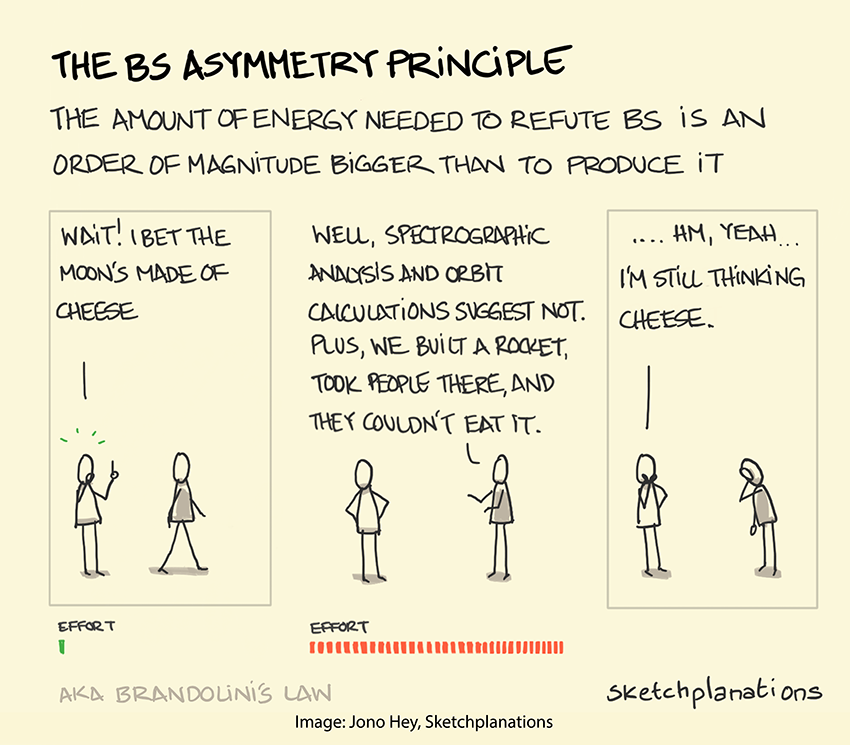

That thought has been updated and refined for the Internet by, of course, a programmer, Alberto Brandolini

The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it. - Brandolini's law

Jono Hey of Sketchplanations has simplified the problem into a visual aid.

Debunking Simplified

Perhaps the best place to begin is with Christopher Hitchens, who offered a rule designed to simplify the process of falsification.

“What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. If you make a claim, it's up to you to prove it, not to me to disprove it.” - Hitchens Razor

It places the burden of evidence on the claim’s advocates, not opponents. Without proof, the burden is not met, the claim unfounded, and no further argument needed. Parenthetically, I try as often as possible to provide sources linked to my assertions, but scoundrels also use links to apparent sources of evidence.

Mike Caulfield, who writes and teaches web literacy, offers three ways to verify those linkages.

- Check for previous fact-checking work – Before spending time verifying a claim, see if reputable fact-checkers like Snopes, FactCheck.org, or PolitiFact have already addressed it, reducing unnecessary effort. If no fact-check exists, proceed to a deeper investigation. (Alas, for my efforts, I am often one of the first to debunk, so no other reputable sources are to be found.)

- Go to the source – Don’t rely on summaries, headlines, or social media posts—trace claims back to their original source. If an article cites another report, follow the link and examine that report directly. This helps identify whether the claim has been distorted, taken out of context, or lacks credible backing. This is the most valuable and time-consuming of approaches, and it is the one I find to be my “go-to.” You can save a bit of time by immediately looking at the source for an article's underlying foundational assumptions or for “givens” that seem different from your current understanding.

- Read laterally – Instead of evaluating a source in isolation, check what other reputable sources say. Search for independent coverage, hopefully, like the articles you find on the American Council of Science and Health’s website. This approach focuses on external credibility and avoids analyzing superficial markers like website design or political slant. (Yes, even those who deceive have kernels of truth within the lie)

For those looking to refute a particular article, there are inherent weaknesses in many science and health articles. More specifically, there are questions on data definitions, validity, and categorizations that do not always require intrinsic knowledge to identify. Often, when weaving valid data points together in the discussion and conclusions, there are jumps in logic or mischaracterizations that make for a more fanciful than factual narrative.

A bitter truth about humans

Unfortunately, there is a weak assumption in my argument and those of Brandolini, Hitchens, and Caulfield – that facts inform our understanding of a particular issue in science and health, that we are logical creatures. Of course, while we are rational, that is not the case for others, e.g., anyone who disagrees. (This is said tongue-in-cheek.)

Here, I turn to the work of Craig Cormick. Few of us get our health and science information directly from primary sources, often locked behind paywalls. Most of us get the news on the Internet, in the case of the oldsters like myself, from websites, blogs morphed into Medium or SubStack, or from video on YouTube (but only rebroadcasts of network news). For the growing majority of us, science and health news comes from social media, where the algorithms favor the emotions of outrage and anxiety over facts. It is impossible to discuss a complex issue when restricted to sound bites, thoughts, and video moments. Research in the science of communicating science teaches us:

- “…factual information is no better at influencing people than information with no factual basis whatsoever.”

- “When we are time poor, overwhelmed with data, uncertain, driven by fear or emotion, we tend to assess information on mental shortcuts or values not facts.” [emphasis added]They turn to “motivated reasoning,” acknowledging what matches their values and beliefs, dismissing the rest.

- “Attitudes that were not formed by logic and facts, cannot be influenced by logic and facts.” While it is possible, with much work and repetition, to change one’s attitude, it is rarely possible to change one’s beliefs. This is often because challenging one’s beliefs is often an existential challenge.

At the heart of it all, the real problem isn’t just misinformation—it’s human nature. We like our facts to be bite-sized, emotion-packed, and conveniently aligned with our pre-existing beliefs. Logical arguments are great, but in the court of public opinion, outrage wins the case before evidence even enters the room. So, while I’ll keep wielding Hitchens’ Razor, Brandolini’s Law, and Caulfield’s verification tactics, I know the battle is uphill.

Source: How “News Literacy” Gets Web Misinformation Wrong

The Science of Communicating Science Craig Cormick

A special thank you for the image to Jono Hey, Sketchplanations