The "five-second rule" suggests dropped food is safe if picked up quickly, based on one of two ideas. First, the morsel is too tasty to have dropped and needs to be eaten regardless, or in some scientific way, bacteria need time to transfer to the morsel.

While there is abundant personal experience, scientific research on this has varied, drawing inconsistent conclusions, using different surfaces, foods, bacteria, and contact times. A study in Applied and Environmental Microbiology hopes to settle on firmer ground.

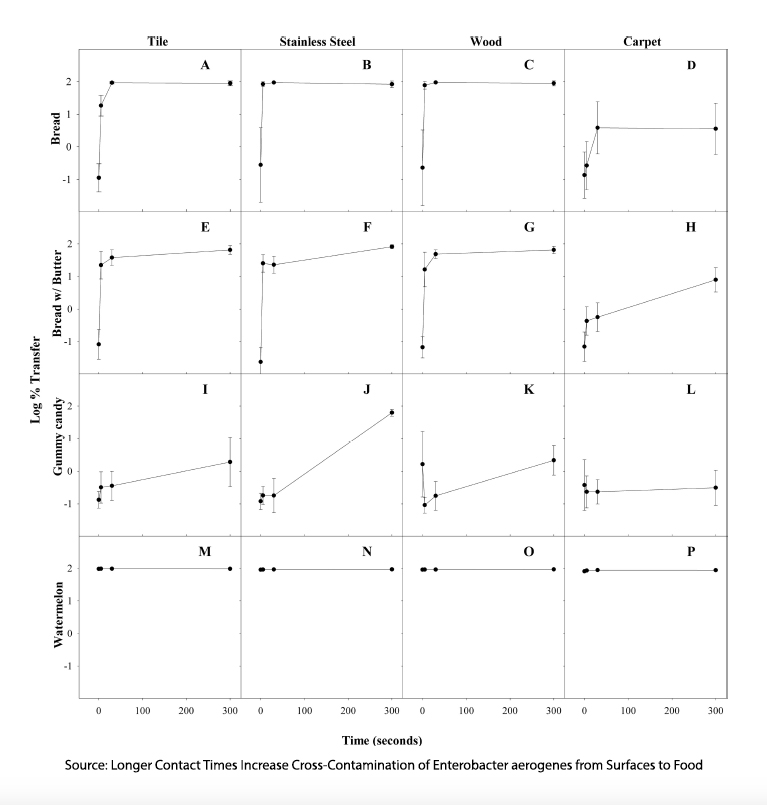

Enterobacter aerogenes, a nonpathogenic bacterium with adhesion characteristics of the more pathogenic Salmonella, were inoculated on four types of surfaces found in our homes: stainless steel, ceramic tile, laminate wood, and carpet and left to dry for five hours. Four food types, watermelon, bread, butter, and gummy candy, were dropped from about 5 inches onto these surfaces and left for 1, 5, 30, or 300 seconds. The outcome was the percentage of bacteria transferred from the surface to the food.

It should be no surprise to those skeptical of the five-second rule that outcomes are entangled in the food being dropped, the surface being impacted, and the contact time between the two.

The vertical axis shows the transfer rate, and the horizontal axis shows the time food and surface were in contact. Each dot represents one of the increasing time intervals. What might we conclude?

- Watermelon, irrespective of surface or time, picks up a great deal of bacteria – Five seconds is far too long for the germophobes amongst us.

- Bread seems to have little transfer in those precious first five seconds, but you have to move quickly; by 10 seconds, most germs are transferred. There is a notable exception for carpeting where you have more time, but there is the possibility of picking up other particulate matter from carpets that may be less pleasing. There is another important conclusion for those engaged in the butter side up or down debate – butter does not seem to have a more pivotal role, making how the bread lands of little scientific concern.

- Gummy candy offered the greatest opportunity for microbiological safety under the five-second rule. A word of caution: the gummy was not already moistened with saliva, so we are talking about candy being dropped on the way to your mouth, not from it.

Longer food contact times result in greater bacterial transfer. Surface characteristics also play a role with polished surfaces, e.g., tile and stainless steel, transferring more bacteria than carpet with nooks and crannies. Similarly, the topography of the food, specifically its moisture, impacts the speed of bacterial transfer.

We will leave the last word to the authors, which speaks not only to their findings but to rules of thumb and models in general.

"Although this research shows that the five-second rule is “real” in the sense that longer contact time resulted in more transfer, it also shows that other factors, including the nature of the food and the surface, are of equal or greater importance. The five-second rule is a significant oversimplification of what actually happens when bacteria transfer from a surface to food."

Source: Longer Contact Times Increase Cross-Contamination of Enterobacter aerogenes from Surfaces to Food Applied and Environmental Microbiology DOI: 10.1128/AEM.01838-16.