For many of us, it is a pain in the ass to make dinner, for ourselves, for two or the stereotypic family of 4.3 and a dog. The free market has provided several answers, from fast food to grab-and-go to a buffet of meal kits in various states of preparation. Academia, in the form of economists, have followed the free marketing of convenience foods and have some observations to share.

- Time constraints play critical roles in shaping household behavior, especially meal preparation, often proving more constraining than monetary costs.

- Convenience, especially concerning travel time, is a big influence when food shopping. That is part of why bodega and 7-11’s do so well.

- Fast food consumption continues to grow, and a third of us eat fast food daily. And each of those meals is about 836 calories, over 40% of the recommended daily intake. One fast food meal a week has been guesstimated to increase our weight by 2 pounds annually.

- From a public health perspective, those fast foods are more energy-dense and higher in fat and sodium than the make-it-at-home counterparts that, with any luck, will contain more whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Consistently eating away from home

A study in the Journal of Urban Economics wanted to explore the tradeoff between time and food; they used traffic congestion to control time and selected food stores as the proxy for food choice.

Does road travel time affect food store choice?

Traffic data comes from Los Angeles, a sprawling traffic jam. Home to six of the top ten most traveled highways and the single urban setting

“…where over 50% of all daily vehicle-mile of travel occurs on an interstate, freeway, or highway, as opposed to other principal arterial roads, minor arterial roads, major collector roads, minor collector roads, and local roads.”

The data comes from the Caltrans Performance Measurement System, or PeMS, which uses automated highway sensors to measure traffic speed and volume hourly. Rush hour traffic in LA doubles the travel time (“a 6-mile trip taking an additional 14 min to complete during evening rush hour.”) For comparison, Washington and Boston clock in at 13 minutes, and New York City, at least before congestion pricing clocked in with an additional 17 minutes. [1]

Drivers returning home have a few meal options. They can return home to a meal or meal prep or pick up something on the way home. Drive-through fast food averages a 5-minute wait; average meal prep is 37 minutes, and food shopping is 41. If time does constrain food choices, then a delay due to traffic may make fast food a “more appealing” tradeoff.

Food Choice was based on food “store” visitation derived from geolocated commuter cell phone data for the stores representing the majority of food acquisition: fast food restaurants, full-service restaurants, convenience stores, and supermarkets.

Over the period from January 2017 to December 2019, the researchers observed 20,475 unique stores with nearly 16 million “store-day” observations. Highway traffic delays were calculated as the minutes per mile lost for speeds slower than 60 mph.

“Traffic congestion exerts a modest yet meaningful influence on fast food restaurant visitation. Specifically, a … increase in weekday traffic delay—around 31 seconds per mile—corresponds to a 1% rise in fast food visits or approximately 1.2 million additional fast food visits per year in Los Angeles County. ”

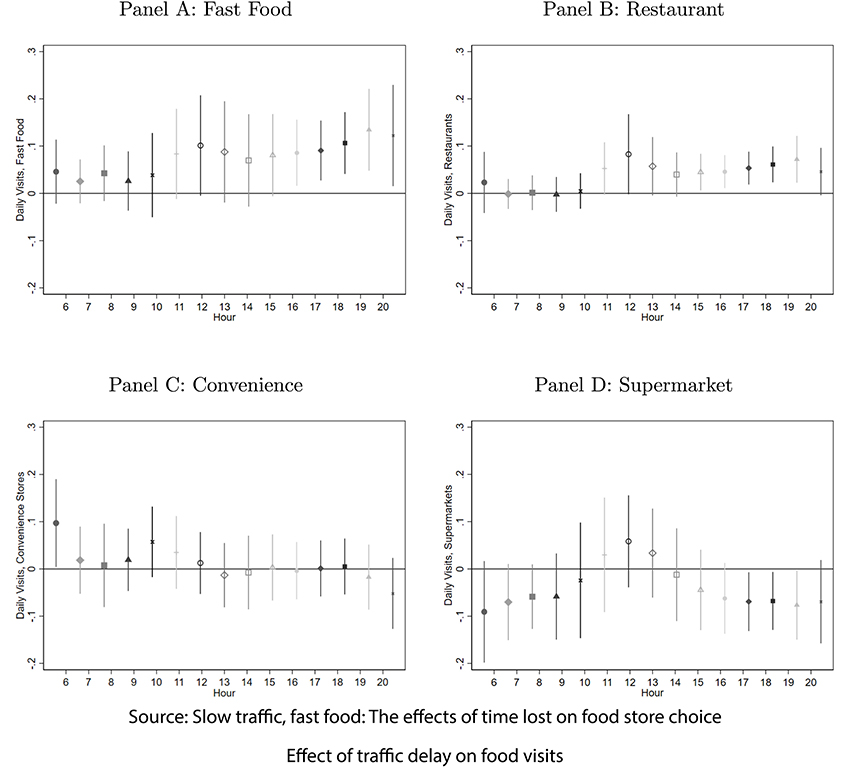

For traffic delays:

- The effect on fast food visitation increased with increasing delays.

- Restaurants had a similar although lesser increase.

- Convenience stores experience no change.

- Supermarkets experience a slight decrease in visits.

- Traffic congestion in the morning had no impact.

- The greatest effect was in the evening, around 7 PM

In addition to traffic delays increasing time constraints, the researchers suggest that traffic congestion bears “emotional costs in the form of stress,” pointing out that stress by itself leads to high-sugar, high-fat, comfort food choices. So perhaps, in addition to the time lost, frustration and low-level road rage contribute to us opting to roll through the fast food drive-throughs.

As it turns out, choosing fast food is more complex than a plot to addict us or because it is deliberately designed to be tasty. Education, in school and on labels and menus, has been the go-to easy fix – of course, that hasn’t moved the needle much. The research points to something we already know: that time constrains our behavior, including food choices. What is made more evident is that the built environment impacts those choices in more ways than simply talking about food deserts or too many fast-food places. Being stuck in traffic reduces our discretionary time and makes fast food if for no other reason than its time savings, a more helpful tradeoff.

“…consumers substitute into less healthy options, on average, in response to traffic.”

Fast food consumption isn't just about convenience, taste, or even price—it’s about time, or more accurately, the lack of it. This study highlights how urban design and transportation infrastructure shape our food choices in ways beyond the usual debates. If traffic congestion makes fast food an even easier default, then the push to return to in-office work could mean more of us swapping home-cooked meals for the drive-thru window.

[1] For those interested, traffic congestion is an international problem. Our most congested city, New York, ranks only 25th globally, behind Bordeaux! Although, we remain ahead of Rome and Mumbai.

Source: Slow traffic, fast food: The effects of time lost on food store choice Journal of Urban Economics DOI: 10.1016/j.jue.2025.103737