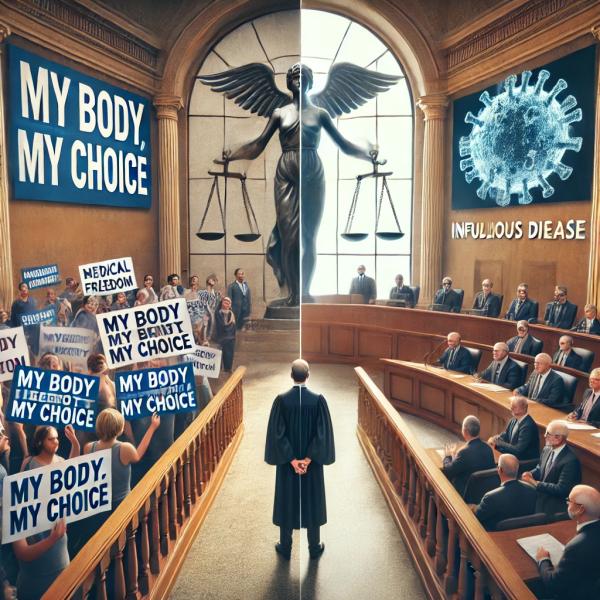

Recent reports document the surging popularity of the “medical freedom” movement, which believes public health regulations interfere with their mantra of “my body, my choice.” This translates into self-serving anti-vax stances, opposition to eliminating religious exemptions for childhood vaccination, and refusal to vaccinate even when the potential vaccinee may expose an unusually susceptible cohort (like nursing home residents) or those more likely to transmit disease (i.e., children) to heightened risks.

All this comes under the rallying cry of Constitutional Liberties and Right to Freedom or philosophical notions of self-ownership and autonomy. The impact already has had serious consequences. Commentators of a recent New York Times article attribute the growth of the Medical Freedom Movement to increased politicization of vaccination and the “ideological flags people embrace.” Its downstream effects portend disaster. But other than waving a public health banner, is there a bioethical argument that furnishes a rebuttal?

States have increasingly bowed to the vaccine resistance in recent legislation. Litigation arguing that any religious belief validates COVID-objections has surged, even as this argument was rejected in earlier cases. When Pastor Henning Jacobson claimed personal liberty to support his vaccine refusal in the “iconic” case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905), the Supreme Court rejected his claim and supported a state’s right to mandate (smallpox) vaccines at the expense of his personal liberty.

That ruling was relied on as recently as 2019 in the NYC measles epidemic, yet all but vitiated only a year later in Roman Catholic Diocese v. Cuomo. (2020). Today, courts increasingly favor the religious plaintiff, a decided difference from the results only a few years ago. And states, while bequeathed the right to make decisions affecting their citizens’ health by the founders, of late, are mostly bowing to “the freedom fighters.”

The right to free speech has also been raised to shield doctors who espouse contrarian medical views, even as state licensing boards seek to censure them, claiming superior jurisdiction to regulate their medical practitioners and licensees. Current trends, politically and legally, seem to favor freedom-espousing libertarians

From a public health perspective, these trends do not bespeak a good resolution.

Is there an alternative approach that would support prioritizing public health over individual rights regarding epidemic infectious diseases We can look to bioethics for guidance, but – spoiler alert, don’t expect much.

The Four Beauchamps and Childress Principles

The classic bioethical rubric doesn’t provide a clear answer. In the US, clinical care is guided by four bioethical principles as articulated by Beauchamps and Childress.

- Autonomy: Respecting the right of individuals to make their own decisions. Incorporated into law as far back as 1914, Justice Cardozo proclaimed: “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body.”

- Beneficence: Doing good (a derivative of the Hippocratic Oath).

- Non-maleficence: Doing no harm, another derivative of the Hippocratic Oath. As Beauchamps and Childress state: “the principle of non-maleficence obligates us to refrain from causing harm to others.”

- Justice: Ensuring fairness.

However, applying these four Bioethical Principles to whether individual liberties “trump” public health provides a confused response.

The principle of autonomy or self-ownership is clear and distinct; the concepts of beneficence and non-maleficence are harder to differentiate. However, these principles can be distinguished by framing the issue as whether a positive or negative act is involved:

“A negative duty requires you to refrain from an action that could cause some form of harm. This relates to non-maleficence, in which we have this same negative duty to refrain from actions which could harm our patients.

A positive duty requires you to actively perform some action to help someone in need. This relates to maleficence which compels a healthcare practitioner to help ill patients in need.” [emphasis added]

Most individuals have no positive duty or obligation to do anything for the betterment of someone else. Healthcare professionals, however, do.

- Under beneficence, an individual has no duty to be vaccinated, even if this practice benefits his neighbor, her family, or society. By contrast, medical doctors are charged with doing good (beneficence) as well as doing no harm (non-maleficence). Spouting rhetoric damaging to public health (e.g., propagating myths like the false autism link to vaccines) would violate both precepts.

- Under non-maleficence, it might be argued that an individual is not at liberty to harm others (or act with substantial knowledge that harm will result from their actions). Failing to be vaccinated during a rampant infectious disease epidemic can be construed as violating that precept, especially for healthcare workers (in contact with the elderly and infirm) and school populations that facilitate disease transmission.

Under the principle of autonomy, libertarians win. Under beneficence, public health wins – but only for health providers, not individuals. Under non-maleficence, which focuses on harm to others- public health wins, even if individual rights suffer. But what about the ethical pillar of justice? That depends on exactly what one means by the term.

Justice

In the healthcare context, this term often refers to distributive justice, i.e., assuring all segments of the population are afforded equal access to life-saving and disease-preventing care. Broadening the notion, however, allows us to consider the concept of basic fairness. Is it “fair” to force individuals to subject themselves to vaccines, which have some, albeit small risk, to prevent harm in the remainder of the population?

Consider a young, healthy 25-year-old male, widely believed not to be particularly susceptible to serious consequences of COVID, but who might be at an increased risk of myocarditis, a recognized risk of some COVID vaccines. Is it “just” (i.e., fair) to compel such an individual to subject himself to this, even small, increased risk - purely for the sake of others? Most people would say no.

The four Beauchamps and Childress principles do not help resolve the matter. Where conflicts exist, some postulate that the resolution must derive from the cultural norms of society. But cultural norms are now divisive and poisoned by politics such that cultural norms don’t even exist to enable answers.

Bioethics and Philosophy

Underlying the Beauchamps and Childress principles are basic philosophical views of morality, the two most prominent being utilitarianism, associated with the work of John Stewart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, and Kantian ethics. In its simplest form, utilitarianism is translated into doing “the greatest good for the greatest number” or maximizing (collective) happiness. Kantian ethics, by contrast, is closely related to deontology from the Greek word deon, meaning "obligation" or "duty," is an ethical system utilizing rules to distinguish right from wrong, driven by the individual’s rational and logical decisions.

Under utilitarianism, maximizing health would contribute to the greatest number of happy (and alive) people, supporting a preference for mandating vaccines and minimizing false rhetoric on health care (e.g., preventing those promoting hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin as COVID treatments from proselytizing based on the current state of the medical literature). Utilitarianism could be construed as making decisions that benefit the collective.

Kantian ethics, by contrast, favors the individual, who is “worthy of dignity and respect,” and is closer to the Libertarian view that “persons should not be used merely as a means to the welfare of others, because doing so violates the right of self-ownership.” [1] Kantian ethics, however, puts us in a quandary. Kant wants to promote making humans good or moral using the individual’s rationality and logic. But what can morality or logic tell us about the superior route – individual medical freedom or promoting public health?

Kantian ethics is strongly tethered to venerating individual freedom, and the freedom he speaks of focuses on the ends- not the means (i.e., that morality requires respecting individuals as “ends in themselves.”] Yet, to reach the Kantian solution requires framing the ends - and that frame differs between Kantians and Libertarians on one hand and utilitarianism and public health promoters on the other.

John Rawls offers a variation of the Kantian system, arguing that under the principles of justice, “a just society respects each person’s freedom to choose his or her own conception of the good life.” [1] Under Rawls and Kantian ethics, which values maximizing the individual's inherent worth, the medical freedom group might well prevail. However, while Rawl and Kant charge the individual with “doing the right thing,” the “right thing” differs based on perspective.

In the debate between medical freedom and public health, the Beauchamps and Childress Bioethical Principles and philosophical frameworks leave us at an impasse, as the ultimate conclusion depends on how the key questions are framed – and by whom — that “who” is often politically-driven. Thankfully, now that the Chevron doctrine has been vitiated, the legal construction of statutory ambiguity governing health issues is now in the hands of courts – not political appointees. There is hope, at least for the law.

For now, the issue still remains: how do we balance individual liberty with collective responsibility in the face of public health crises? Stay tuned as we continue to explore different approaches.

[1] Michael Sandel, Justice, What’s the Right Thing to Do?