“In truth, that shapeless schmatta that ties in the back, leaving one’s rear end hanging out for the world to see, is… one of the most unappealing items of clothing ever made. … The patient gown … was essentially designed to be the most efficient way to give patients a modicum of physical privacy while allowing doctors and nurses ease of access for examination and treatment…”

- Vanessa Friedman, NY Times

Harsh words. Coming from a fashionista, it is understandable, but researchers have also chimed in, the latest being an equally harsh criticism of the gowns from an ethical viewpoint (?). In this instance, the why is a more important lesson than the what. Spoiler alert: the gowns are a scapegoat.

“The apparel oft proclaims the man” – Polonius, The Tragedy of Hamlet

The current research letter examined the psychological impact of wearing a patient gown during an office visit. 74 participants “underwent a standard hospital admission interview at a medical school clinic (medical history and vital signs check).” Half were randomized to wear a gown. In addition to the usual demographics, the researchers captured the participants' total words during the examination, focusing on emotional words and first-person pronouns, e.g., I and My, and their experience of “dehumanization” based on a questionnaire.

Those participants wearing gowns “reported feeling significantly more dehumanization” than the control group wearing their own clothing. All the comments about gowns were negative, leading the researchers to conclude:

“This randomized clinical trial supports observational findings that patient gowns increase feelings of vulnerability and disempowerment.”

That is a great deal of harm to attribute to a piece of clothing. I personally can’t remember the last time I wore a patient gown in the office, and as an oldster, I have a lot of experience, so we might be inclined to dismiss the study. However, a slightly older, more in-depth study comes to a similar conclusion.

The researchers began with qualitative interviews with 10 individuals with “lived experience of wearing hospital clothing,” people with chronic health conditions making hospitalization a more frequent occurrence. Several “themes” emerged from those interviews. Wearing a hospital gown:

- Symbolized a transition from healthy to sick.

- Removal of personal items, i.e., jewelry and phones, stripped participants of their identity, creating uncertainty, vulnerability, and discomfort.

- The obligatory requirement to wear the ground reflected a lack of personal agency and control compared to medical professionals – wearing the gown was disempowering

- The gown’s design was undignified. Wearing the gown emphasized the need for protection, dignity, and safety

“Wearing hospital clothing (most commonly the hospital gown) was associated with symbolic embodiment of the ‘sick’ role, relinquishing control to medical professionals, and emotional and physical vulnerability for people living with a chronic health condition.”

The researcher then sought to generalize those themes to the general population, “given that the majority of adults may have had to wear the hospital gown at some point in their life trajectory.” 928 participants completed an online survey on their experience with hospital gowns.

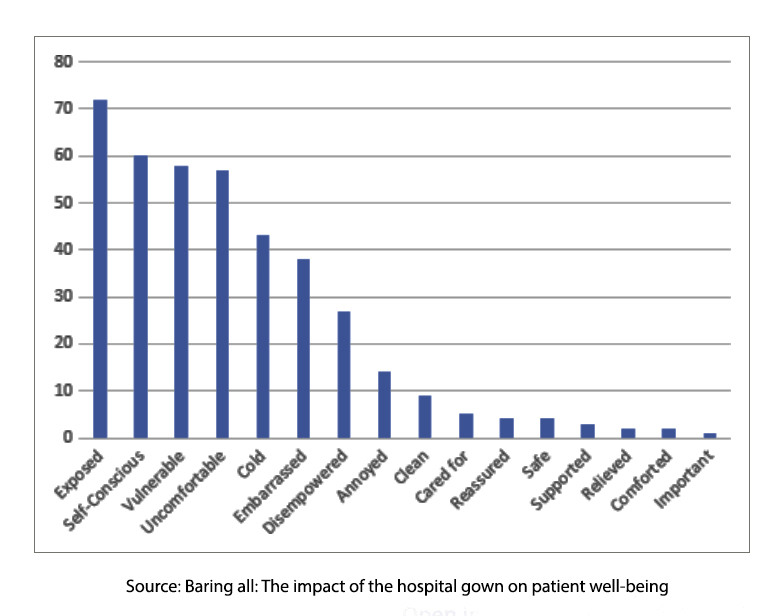

These participants, too, felt “exposed, self-conscious, vulnerable, uncomfortable, cold, embarrassed, and disempowered.” The researchers liken the hospital gown to the uniform worn by prison inmates as a “means of control,” creating a “hierarchical power dynamic, between the clothed medical professional and the semi-stripped patient.”

Liminal Spaces

There are moments in our lives that are transformative, liminal events and spaces live within those moments when we are both in the past and present. The Sweet sixteen, Bar Mitzvah, and the Quinceañera are all coming-of-age luminal moments. We also have luminal spaces where these transformative events occur, e.g., the Baptismal font, the aisle and chuppah for weddings, the stage at graduation, and even airports. Airports are a good example because the luminal experiences are not always good (delays, lost baggage).

In healthcare, luminal events and spaces are markers of our passage from certain to uncertain and from ease to dis-ease. Simply being a patient in a hospital involves vulnerability and disempowerment. Projecting those unsettling emotions onto gowns, or the way a waiting or examination room is laid out, is in large part a displacement mechanism. The researchers’ data is correct, but they err when they, like patients, construct a narrative that the fault lies with, in this instance, the design of the gowns.

Redesign of a hospital’s liminal space may make us “feel” somewhat more at ease, but no choice of material, color, furniture, or decor will overcome the liminal emotions hospitalization surfaces. Similarly, word choices like “patient’s journey” or “shared decision-making” may reflect a well-intentioned but doomed effort to make one’s care seamless and friction-free.

Hospital gowns are an easy target for criticism, but they’re merely symbols of the deeper challenges that come with the liminal experience of being a patient—caught between health and illness, control and dependence. While redesigning these gowns might offer a modest improvement in comfort, it won’t erase the existential unease that accompanies medical care. As both a physician and patient, I am unsure whether “true empowerment,” equality between physician and patient, is possible or, dare I suggest, always desirable.

Sources: Patient Gowns and Dehumanization During Hospital Admission JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.49936

Baring all: The impact of the hospital gown on patient well-being British Journal of Health Psychology DOI:10.1111/bjhp.12416